Step 1: Choose a Topic I’m going to flat out assume that over the past year, you’ve read at least 100 new (published in past three years) nonfiction picture books. If you haven’t, stop right here and start putting books on hold at your library. This info will be here waiting for you when you finish your reading…

Great, you’re back!

Choosing a topic for your nonfiction picture book is your first step, usually. (I say usually because I sometimes choose the form/structure first, but that’s not really normal.) This is the “What” of three important elements of your book. (What? So what? and Now what?)

Forget “write what you know.” Instead, write what you are excited about or curious about! You will be spending a lot of time with this topic over the next several months or years, so you need to care about it.

However, just because you care about it doesn’t mean kids or editors will care about it. Here are a few things to consider.

Kid Appeal: Your topic has to appeal to kids as well as yourself! One of the great joys of reading nonfiction picture books, for me, is discovering that a topic is way more interesting than I initially thought. And that can definitely happen. But in general, it’s great if your topic has obvious, immediate appeal to kids. If it relates to their lives somehow. Big machines, creepy bugs, amazing animals, cookies—these are examples of topics kids relate to. They see them in real life or on TV. They know what these things are. They are drawn to them. They have an emotional reaction to the topic—whether that’s excitement, fear, or happiness.

Topics without immediate kid appeal might still work, but finding just the right angle will be key. (More on that in a future segment.) For instance, taxes, swollen feet, and how to hang holiday lights might all interest some adults. But picture book readers? Not so much.

Competition: Your topic must be fresh to stand out from the competition. Go to Amazon and do a search for children’s books on your topic. Are there 20? 350? None at all?

Some topics have been covered so much that it would be really difficult to sell another book on the topic. When I search Amazon for children’s nonfiction picture books for ages 3–5 about “animals,” more than 7,000 results appear. Seven. Thousand.

When I narrow it down to “dogs,” there are still more than 2,000 results.

When I switch to “platypus,” there are two results.

You might be able to sell a dog nonfiction picture book if you come up with a totally fresh approach, but there’s probably more room for a platypus book.

Curriculum: Curriculum connections only matter if your picture book is going to be for ages 5–9, rather than the more traditional 2–5‑year-old audience. But if your topic ties in to something kids study at school, that’s good to know and might help you decide which age range to target. (More on that soon.) It also might help sell your manuscript, when it comes time.

DO THIS NOW

- Brainstorm a list of possible topics to write about. You can start with general topics—cars, sand, the sun, Abraham Lincoln…whatever you’re curious about or passionate about. Can you list 50 topics? Give it a try.

- Now go back and circle or highlight the 10 that most interest you that also might not have as much competition as “animals.”

- Reread your list of 10. Which one is whispering to you right now—pick me! Let’s start with that one.

Step 2: Wonder So, you have chosen a general topic. This next step is one a lot of people skip over, but I think it’s crucial. I want you to wonder about your topic. Even if you already know a lot about your topic. Even if you think you already know your specific angle. When you wonder, approach your topic as if you know nothing about it. Make your mind a blank slate. Sometimes what we already know actually gets in the way of being creative. So, pretend to be a child, one who knows very little about this topic. Grab a coffee table book or do a Google search for images of your main topic. And then start wondering. Jot down everything that occurs to you. For me, this will mostly be questions, but sometimes it’s observations, too—things I never noticed before. I’m going to demonstrate wondering about a topic I know little about and care even less about: trucks. Here’s one page of my search results:

Step 2: Wonder So, you have chosen a general topic. This next step is one a lot of people skip over, but I think it’s crucial. I want you to wonder about your topic. Even if you already know a lot about your topic. Even if you think you already know your specific angle. When you wonder, approach your topic as if you know nothing about it. Make your mind a blank slate. Sometimes what we already know actually gets in the way of being creative. So, pretend to be a child, one who knows very little about this topic. Grab a coffee table book or do a Google search for images of your main topic. And then start wondering. Jot down everything that occurs to you. For me, this will mostly be questions, but sometimes it’s observations, too—things I never noticed before. I’m going to demonstrate wondering about a topic I know little about and care even less about: trucks. Here’s one page of my search results:

Laura’s Wonders About Trucks

- Who invented trucks?

- How long can a truck be before it needs more than 4 wheels?

- Are semis without their trailers lonely?

- Do long-distance drivers really sleep in the cabs of their trucks?

- Why does cab mean both the front/driver area of a truck AND a taxi? Which came first?

- Who invented dump trucks?

- Why do some dump trucks dump to the side and others out the back?

- How much do trucks weigh? Can one weigh more than a house?

- Who invented the first truck, and why?

- What are the differences between, say, a farm truck and a delivery truck?

- What are the weigh stations for on highways? Why do trucks get weighed? Is it to make sure they aren’t smuggling?

- How heavy can a truck be before it would start to crush a road?

- Why do we have monster trucks?

- What kinds of trucks save lives? (fire trucks, ambulances…)

- What’s it like to be a trucker? Especially a long-haul trucker?

- Are big rigs hard to drive?

- What are some of the most amazing things that have spilled out of trucks onto roads/highways?

- What different things do people haul in pickup trucks?

- What are the safety rules about riding in trucks?

- Are there celebrities in the monster truck world?

- What if you’re too short to climb up in a truck?

- What bad things have people used trucks for? (human smuggling)

- What’s the biggest truck in the world?

- Why are trucks so loud?

- How come trucks tip over?

That’s about five minutes worth of wondering. The images I got are pretty bland, and I bet if I dug deeper into the search results, I’d find more compelling images that would bring up more wonders for me. Note that many of these sound boring or inappropriate for picture books. That’s OK! The point here is just to brainstorm! Now I’m going to go back through my wonders and choose a few that interest me enough that I might want to actually look up the answers or do more thinking about them. Here are the ones I chose:

- Do long-distance drivers really sleep in the cabs of their trucks?

- How much do trucks weigh? Can one weigh more than a house?

- How heavy can a truck be before it would start to crush a road?

- What’s it like to be a trucker? Especially a long-haul trucker?

- Are big rigs hard to drive?

- What are some of the most amazing things that have spilled out of trucks onto roads/highways?

- What’s the biggest truck in the world?

Looking at those, I see that most relate to truck extremes or to being a trucker. Both of those could morph into picture books, so I’m ready to move onto my next step: research.

DO THIS NOW

- Take your chosen topic and surround yourself with images related to it.

- Spend some time wondering with an open mind.

- Mark the wonders/notes that most appeal to you and notice if they connect in any way.

Step 3: Research This is my first phase of research, though I will come back to researching many times over the course of writing a nonfiction picture book. And, honestly, I would usually already know a little bit about a topic because I would have chosen a topic I’m interested in. Since I chose trucks as my example topic, though, I’m starting from scratch! At this first research stage, I’m looking at several kinds of resources:

Step 3: Research This is my first phase of research, though I will come back to researching many times over the course of writing a nonfiction picture book. And, honestly, I would usually already know a little bit about a topic because I would have chosen a topic I’m interested in. Since I chose trucks as my example topic, though, I’m starting from scratch! At this first research stage, I’m looking at several kinds of resources:

- general online articles (I would never use Wikipedia as a bibliographic source, but it’s great to get a general sense of a topic, and it can point me toward more credible resources)

- a book or two for adults on the topic—or browsing through magazines on the topic if there are any published on it

- picture books on my topic published in the past five years or so

- videos on YouTube

And here’s what I’m looking for:

- basic background information

- what approaches have already been done to death in picture books

- what are some areas that might connect well to kids?

(I’m looking for these areas because my next step will be choosing my angle.) Here are a few of the concepts that I noted in my research:

- The defining characteristic of a truck is that it can haul cargo.

- Cab and cargo area are two distinct places.

- Monster trucks are extremely loud and really big!

- Wide variety of sizes and materials, plus specialized equipment attached to them.

There was LOTS more that I read, even in my basic research, but most of it was very complicated (to me, anyway) and not really picture book material. From looking at picture books, I got a sense of what is being done for this age. Here are just a few of the books I looked at.  Some of these are written for the educational market and sold mostly to school libraries. You can tell those if you recognize the educational publisher names, if you see the copyright is in the name of the PUBLISHER, not the author, or if you see the books are part of a series. I’ve written many books for the educational market, but it’s not what I’m trying to do here.

Some of these are written for the educational market and sold mostly to school libraries. You can tell those if you recognize the educational publisher names, if you see the copyright is in the name of the PUBLISHER, not the author, or if you see the books are part of a series. I’ve written many books for the educational market, but it’s not what I’m trying to do here.

When I look at “bookstore” books, or “trade market” books, I see mostly books that name the different kinds of trucks and other big vehicles. Those are for very young kids and are really concept books.  I also see books that involve a fictional element. SUPERTRUCK, which I love, shows different types of trucks and the work they do. But the fiction element of a garbage truck turning into a superhero snowplow truck after a blizzard is the heart of the story. It’s not really a truck book. It’s a book about how even the unsung person (like a kid) can be a hero.

I also see books that involve a fictional element. SUPERTRUCK, which I love, shows different types of trucks and the work they do. But the fiction element of a garbage truck turning into a superhero snowplow truck after a blizzard is the heart of the story. It’s not really a truck book. It’s a book about how even the unsung person (like a kid) can be a hero. ![Supertruck (Ala Notable Children's Books. Younger Readers (Awards)) by [Savage, Stephen]](https://i0.wp.com/images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51zUtsATPsL._SX260_.jpg?w=800&ssl=1) OLD MACDONALD HAD A TRUCK uses the song to introduce a bunch of types of trucks (with varying degrees of success in the meter). Cool idea. BIG RIG involves a talking big rig—fun! But as far as nonfiction with no fictional element, it becomes pretty clear to me that most of the books at a typical picture book age (3–5) really focus on just naming the different kinds of trucks with images or perhaps a word or two describing what different trucks do. Trucks are complex enough that books that really try to explain anything about how they work seem to mostly be done by educational publishers. Because I’m not truly going to write a picture book about trucks, I am doing fairly shallow research here. I’m really trying to get a sense of what publishers think works for different age groups and what has been done a lot so that I can think about what I can offer that’s different.

OLD MACDONALD HAD A TRUCK uses the song to introduce a bunch of types of trucks (with varying degrees of success in the meter). Cool idea. BIG RIG involves a talking big rig—fun! But as far as nonfiction with no fictional element, it becomes pretty clear to me that most of the books at a typical picture book age (3–5) really focus on just naming the different kinds of trucks with images or perhaps a word or two describing what different trucks do. Trucks are complex enough that books that really try to explain anything about how they work seem to mostly be done by educational publishers. Because I’m not truly going to write a picture book about trucks, I am doing fairly shallow research here. I’m really trying to get a sense of what publishers think works for different age groups and what has been done a lot so that I can think about what I can offer that’s different.

DO THIS NOW

- Read a very general encyclopedic online article on your topic.

- Read an adult book on your topic (or a number of in-depth magazine articles).

- Do an Amazon search for picture books on your topic that have been published in the past 5 years. Put them on reserve or on interlibrary loan through your library. (Here’s one place where picture book e‑books are so convenient! I hate picture book e‑books for actual reading. But for research purposes like this, they’re fast and fabulous.)

- Watch 10 YouTube videos related to your topic.

- Summarize your findings. What did you learn? What most interested you? Which facts do you think have the most kid appeal? Are there clear trends in how your topic is treated? Have a zillion picture books been published with your topic? Or zero picture books? Both can be a sign of trouble, but neither is absolute cause to give up. The goal is to feel like you have a good understanding of how your topic has already been treated in picture books in the recent past.

NOTE: Even if you already know a lot about your topic, it’s worth doing this survey. There is always more to learn, and exposing yourself to more general info might actually help you get a better big picture oversight on a topic you know intimately.

Step 4: Pick an Angle Your topic is your subject. But you need more than a subject. Most picture books have a specific approach to a topic. They are not encyclopedic, trying to tell everything about some subject. There are two reasons for that: One, picture books are short! Two, and more importantly, encyclopedic approaches are boring. If a reader doesn’t care about trucks, for instance, a picture book full of general truck information is not going to appeal to that reader. (And if a reader does care about trucks, a picture book with an encyclopedic approach is unlikely to show the reader anything new. Especially on a popular topic.) So your angle is what specific aspect of the topic you choose to focus on in your picture book. As I think about angles for my theoretical truck book (and keeping in mind I have only done the very shallowest research at this point), I think my angle is going to be what it’s like to be a long-distance trucker. The topic is trucks. That’s the WHAT. But the angle is sort of the SO WHAT. It’s specific enough to hopefully engage readers and draw them in. Here are some more examples from my previous books.

Step 4: Pick an Angle Your topic is your subject. But you need more than a subject. Most picture books have a specific approach to a topic. They are not encyclopedic, trying to tell everything about some subject. There are two reasons for that: One, picture books are short! Two, and more importantly, encyclopedic approaches are boring. If a reader doesn’t care about trucks, for instance, a picture book full of general truck information is not going to appeal to that reader. (And if a reader does care about trucks, a picture book with an encyclopedic approach is unlikely to show the reader anything new. Especially on a popular topic.) So your angle is what specific aspect of the topic you choose to focus on in your picture book. As I think about angles for my theoretical truck book (and keeping in mind I have only done the very shallowest research at this point), I think my angle is going to be what it’s like to be a long-distance trucker. The topic is trucks. That’s the WHAT. But the angle is sort of the SO WHAT. It’s specific enough to hopefully engage readers and draw them in. Here are some more examples from my previous books.

| Title | What (Topic) | So What (Angle) | |

| If You Were the Moon | The moon | The different things the moon does, shown through comparisons to child behaviors | |

| A Leaf Can Be… | Leaves | Leaves do a lot of different things you might not have thought of before | |

| BookSpeak! | Books | What would books and parts of books say if they could speak? | |

| Stampede | Kids at school | How do kids at school behave like different animals? |

DO THIS NOW

- Look back over your notes so far.

- Think about what fascinates YOU about your topic.

- Think about what hasn’t already been done a lot.

- Choose your angle!

NOTE: Don’t put a ton of pressure on yourself! You might end up coming back to change this later, and that’s OK. But you need to choose an angle now in order to move forward.

Step 5: Be Effect-ive Now you’ve got your topic (your WHAT) and your angle (your SO WHAT). The third important element of your topical triangle is the NOW WHAT. That’s the effect you want your book to have on your readers.

Step 5: Be Effect-ive Now you’ve got your topic (your WHAT) and your angle (your SO WHAT). The third important element of your topical triangle is the NOW WHAT. That’s the effect you want your book to have on your readers.

- Do you want them to feel a specific emotion about your topic?

- Do you want to change their opinion about something?

- Do you want them to take specific actions?

- Do you want to inspire them to learn more about your topic?

- Do you want them to feel calm and ready for bed?

All of these effects, and more, are excellent goals. And your book might lead to more than one of them. But knowing your primary goal, the effect you want to have on your reader, can be really helpful in the writing and revising of your nonfiction picture book. Note: Sometimes, this changes over the course of writing your book, and that’s totally part of the process! And sometimes it emerges organically as you write. Again, totally fine. Writing your nonfiction picture book is not a perfectly linear process. You will go through many of these steps more than once. You will circle back, gnash your teeth, delete chunks, change your mind, wonder why you ever picked this topic in the first place, and so on. And eventually, I hope, you will end up with a manuscript you are proud of! OK, back to effects. Here are the SO WHATs of my nonfiction picture books for the trade market so far.

| Title | What (Topic) | So What (Angle) | Now What (Effect) |

| Snowman-Cold=Puddle (coming in 2019) | Spring changes | Look closely at the elements of different relationships in spring and represent them in surprising equations/poems | Start looking for cause and effect in nature (secondary: learn to express relationships in metaphors) |

| Meet My Family | Animal families | Meet animal families that exhibit lots of the same structures that human families do | Come to an a‑ha moment of accepting that many family structures can be the “right” one |

| If You Were the Moon | The moon | The different things the moon does, shown through comparisons to child behaviors | Feel wonder about the moon’s influence on us |

| A Leaf Can Be… | Leaves | Leaves do a lot of different things you might not have thought of before | Feel wonder and awe about ordinary parts of our natural world |

Here’s a confession: I didn’t really realize the NOW WHAT of my Can Be… books until A Leaf Can Be… had been out for a while. I subconsciously knew, I guess, because I put it right there in the ending with directions to the child reader:

A leaf is a leaf, a bit of a tree. Now go and discover what else it can be.

But still, I really thought the purpose of my book was to show the different things leaves could be. Which it does. But the NOW WHAT, the really super-important part of the book, didn’t become clear to me until I started getting feedback from readers and teachers. Then I had my own a‑ha moment about what I really wanted readers to take away from my book. Now I think about the NOW WHAT as part of my writing process instead of waiting for readers to hit me over the head with it!

But still, I really thought the purpose of my book was to show the different things leaves could be. Which it does. But the NOW WHAT, the really super-important part of the book, didn’t become clear to me until I started getting feedback from readers and teachers. Then I had my own a‑ha moment about what I really wanted readers to take away from my book. Now I think about the NOW WHAT as part of my writing process instead of waiting for readers to hit me over the head with it!

DO THIS NOW

- Picture a child reading your book with a parent or teacher. When the book is finished, what does your reader do? Does he excitedly repeat the amazing lion facts he learned? Does she start playing computer scientist make-believe, imitating the hero of your biography? Does he bug his mom or dad to start a family compost bin?

- Write down your SO WHAT: When a reader finishes my book about __________________, I want him or her to ____________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________.

- Remember that you are not locked into stone with this SO WHAT. It’s just a starting place for you that will help you make some decisions moving forward.

Step 6: Structure It This is one of my favorite parts of writing a nonfiction picture book: coming up with the structure. The structure is HOW you’re presenting your info in order to achieve the effect you want. You have a lot of options! Here are just some of the structures you might choose from, along with an example or two of each one.

Step 6: Structure It This is one of my favorite parts of writing a nonfiction picture book: coming up with the structure. The structure is HOW you’re presenting your info in order to achieve the effect you want. You have a lot of options! Here are just some of the structures you might choose from, along with an example or two of each one.

Chronological Narrative: If you’re writing a biography or a book about a historical event, chances are you’ll present the information in a linear narrative, relating the events in the order in which they happened. (That’s not guaranteed, though.)

How-To: If you’re teaching kids how to do something, this is the structure you want.

List/Survey: If you’re sharing broad, parallel info about a topic or many examples of one kind of thing, you might do it in a list structure.

Explanation/Exposition: This encompasses most picture books written in paragraphs that don’t fit any of the other specific categories.

Ficformation (sometimes called informational fiction): This is where you embed your information inside a fictional framework. Sometimes the Library of Congress calls these books fiction, other times it calls them literature (which is LOC-speak for nonfiction). My If You Were the Moon has a moon that talks, but it was classified as nonfiction, which was quite a surprise! I’m totally good with that, though, as its main purpose is to share info about the moon.

Reader Experience: In these books, you somehow make your reader experience whatever the topic is.

Riddles:

Q&A:

Within each basic structure, there are many variations you can explore. You might have elements of a problem/solution structure within your exposition. Or you might compare two elements or people in a compare-and-contrast exposition book. You might write a chronological biography that incorporates some how-to or list elements. So, don’t feel constrained. Instead, just think about your topic, your angle, and the way you want to affect your reader. Which structure jumps out as a good fit for you? Try that first! And know that you might come back to this step and try several more structures before you find the just-right one.

One other thing to think about as you consider structures is whether you will use layered text and/or backmatter. Layered text is when you have a main text and then a secondary text on the same spread. Backmatter is when you add extra information at the end of the book, so as not to interrupt the flow or language of your main text. Here are a few books that use layered text and/or backmatter.

I have another post where I share my brainstorming of approaches for a possible picture book about boats. You might find that helpful to look at. And Author Melissa Stewart has many awesome posts about different kinds of nonfiction books for kids, and it’s well worth your time to explore her site/blog. Start here at http://celebratescience.blogspot.com/search/label/Nonfiction%20Text%20Structure to read her posts that are tagged Nonfiction Text Structure. Have fun!

DO THIS NOW

- Choose three structures that appeal to you.

- For each one, work through how you might present your information using that structure. What would work well? What challenges would that structure present?

- Choose the one that seems most promising.

- Find at least 5 other nonfiction picture books using the general structure you’ve chosen and read them.

Step 7: More Research Now that you’ve figured out what you want to focus on and what you really want to leave your reader with, you probably have a much better idea of what information you need. A cheery 40-word introduction to trucks for toddlers obviously requires a totally different kind and depth of research than an 1,800-word biography of a scientist for 3rd graders. So, dig in. As you research, remember to consult a wide variety of sources, including:

Step 7: More Research Now that you’ve figured out what you want to focus on and what you really want to leave your reader with, you probably have a much better idea of what information you need. A cheery 40-word introduction to trucks for toddlers obviously requires a totally different kind and depth of research than an 1,800-word biography of a scientist for 3rd graders. So, dig in. As you research, remember to consult a wide variety of sources, including:

- books for adults

- highly credible organizations’ websites

- academic journals

- personal interviews

- magazine and newspaper articles

- primary source materials (diaries, interviews, autobiographies, etc.)

- personal experience

- videos

- recordings and photographs

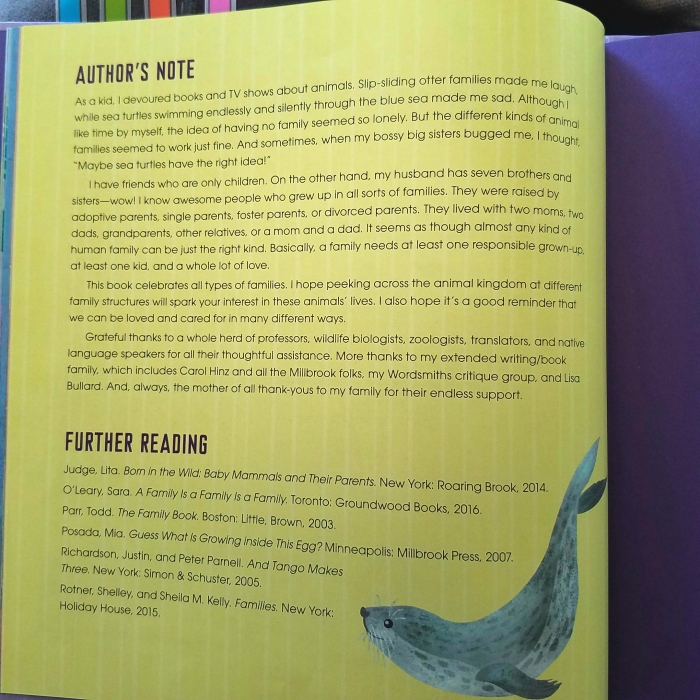

Make sure you’re keeping track of what information you find and where you find it. You might use Evernote, OneNote (what I’m currently using), Scrivener, index cards, or some other system entirely. That’s fine, as long as you have some system! You need to be able to identify where you found each fact in your manuscript, particularly anything that is more specific than the info typically found in an encyclopedia article. And don’t underestimate the scope of your research. My 2018 picture book, Meet My Family!, has a rhyming main text of only about 130 words. The sidebars are about 800 words altogether. And then there’s backmatter. Still, this is not a super in-depth book, but the bibliography I turned into my editor had 79 entries. 79. If you’re particularly fond of research, you might want to give yourself a deadline, at which point you’ll start writing regardless of whether you’re “finished” with your research. Otherwise, you might find yourself researching forever and never actually writing.

Make sure you’re keeping track of what information you find and where you find it. You might use Evernote, OneNote (what I’m currently using), Scrivener, index cards, or some other system entirely. That’s fine, as long as you have some system! You need to be able to identify where you found each fact in your manuscript, particularly anything that is more specific than the info typically found in an encyclopedia article. And don’t underestimate the scope of your research. My 2018 picture book, Meet My Family!, has a rhyming main text of only about 130 words. The sidebars are about 800 words altogether. And then there’s backmatter. Still, this is not a super in-depth book, but the bibliography I turned into my editor had 79 entries. 79. If you’re particularly fond of research, you might want to give yourself a deadline, at which point you’ll start writing regardless of whether you’re “finished” with your research. Otherwise, you might find yourself researching forever and never actually writing.

DO THIS NOW

1) Make a list of questions that you already know you need answers to.

2) Also list any subtopics of your topic that you just need to learn more about.

3) Decide on your system for organizing and recording notes and sources.

4) Get started!

Step 8: Draft It All the steps so far have been logical and organized and, well, not that intimidating. But now it’s time to just dive in. Write a first draft. That’s it. Just do it. Don’t judge it. Don’t worry about any of the things you’ve thought about and planned out. Review it all, then set it all aside and just write.

Step 8: Draft It All the steps so far have been logical and organized and, well, not that intimidating. But now it’s time to just dive in. Write a first draft. That’s it. Just do it. Don’t judge it. Don’t worry about any of the things you’ve thought about and planned out. Review it all, then set it all aside and just write.

DO THIS NOW

1) Write a first draft. (You didn’t expect anything else, right?)

Step 9: Find the Arc From here on out, almost everything is about taking that draft and making it better. (Or at some point, perhaps it will be about throwing that approach out and doing a new first draft with a whole new structure, angle, etc. But don’t worry about that right now.) One thing to ask when looking at your draft is: where is my arc? Sometimes nonfiction has a narrative arc, if you are writing a biography or other chronologically told story. And in that case, you will use a narrative arc of increasing tension to a great climax/resolution, just as in fiction writing. But many nonfiction picture books don’t have a narrative arc. However, your BOOK must still have an arc, even if it is non-narrative nonfiction. It took me a while to learn this. That even if your book is not a story, you have to find a way to guide your reader through the journey of the information you’re sharing with them. That arc will evoke certain emotions in your readers. And it should leave them with a clear sense of being in the hands of a trusted guide who knows what he or she is doing. A guide who has a plan. A guide who is not just tossing information at them with no overall organization. When they hear the first lines of your book, your readers should have some sense of beginning a journey. When they hear the final lines, they should feel satisfied and know the journey is coming to an end. A lot of this, I learned from editors. Here are some examples of the arcs in my picture books.

Step 9: Find the Arc From here on out, almost everything is about taking that draft and making it better. (Or at some point, perhaps it will be about throwing that approach out and doing a new first draft with a whole new structure, angle, etc. But don’t worry about that right now.) One thing to ask when looking at your draft is: where is my arc? Sometimes nonfiction has a narrative arc, if you are writing a biography or other chronologically told story. And in that case, you will use a narrative arc of increasing tension to a great climax/resolution, just as in fiction writing. But many nonfiction picture books don’t have a narrative arc. However, your BOOK must still have an arc, even if it is non-narrative nonfiction. It took me a while to learn this. That even if your book is not a story, you have to find a way to guide your reader through the journey of the information you’re sharing with them. That arc will evoke certain emotions in your readers. And it should leave them with a clear sense of being in the hands of a trusted guide who knows what he or she is doing. A guide who has a plan. A guide who is not just tossing information at them with no overall organization. When they hear the first lines of your book, your readers should have some sense of beginning a journey. When they hear the final lines, they should feel satisfied and know the journey is coming to an end. A lot of this, I learned from editors. Here are some examples of the arcs in my picture books.

| Title | What (Topic) | So What (Angle) | Arc |

| Meet My Family! | Animal (and human) families | There are many kinds and structures of families, and they can all work! | The arc is subtle in this one, but I was thoughtful in not wanting too many slightly sad comments about families (the raccoon who’s never met his dad, for instance) to be in a row. I wanted a bouncy pace full of contrasts (between animals on the same spread and also from one spread to the next), and I didn’t want to forecast the ending—which features human families. |

| If You Were the Moon | The moon | The different things the moon does, shown through comparisons to child behaviors | I wrote the opening scene between the girl and the moon at editor Carol Hinz’ suggestion. I also broadly grouped the moon’s actions into: · Interactions at a planetary level · Affecting Earth’s plants/animals · Impacting/interacting with humans Ended with the lullaby line and the girl from the opening scene falling asleep, giving it a bit of a bedtime story arc, too. |

| A Leaf Can Be… | Leaves | Leaves do a lot of different things you might not have thought of before | It begins in spring and travels throughout the year to winter. |

| BookSpeak! | Books | What would books and parts of books say if they could speak? | I wrote the opening poem, “Calling All Readers,” at editor Daniel Nayeri’s request, so that the book would have an introduction of sorts. And the book ends with “The End.” So the journey through the book very subtly echoes the act of reading a book. |

| Stampede! | Kids at school | How do kids at school behave like different animals? | This collection was a random assortment of school day poems, until editor Jennifer Wingertzahn suggested a chronological arc. So the first poem starts in the school yard before the bell rings, and the final poem is the stampede of kids leaving school at the end of the day. |

DO THIS NOW

1) Read your draft. Mark where you see moments of tension. Mark where those moments of tension are resolved.

2) Or identify what is the thread through your manuscript that a reader can follow. How does each piece of information logically follow the piece before? Is it chronological (by year, season, day, hour)? Is it in cause and effect, each step coming as a direct result of the step before? Are the facts grouped logically somehow so that, once you identify what the thread is, you can follow it through the whole manuscript, using it to hint at what will be next?

3) If you can’t find tension or a thread, then arc is something you need to think deeply about and figure out how to imbue your manuscript with it.

4) Try on different arcs, writing new drafts for each one.

Step 10: Raise Your Voice Another aspect of your manuscript to think about is voice. What is the tone of your manuscript? Nonfiction is not neutral. It is not voiceless. It is not boring. Look again at the effect you’re aiming for. For instance, if you want your reader to be wowed by a topic, then you might use a voice of awe or excitement, or a very dramatic voice. Here are just a few examples of voice from some of my favorite nonfiction picture books:

Step 10: Raise Your Voice Another aspect of your manuscript to think about is voice. What is the tone of your manuscript? Nonfiction is not neutral. It is not voiceless. It is not boring. Look again at the effect you’re aiming for. For instance, if you want your reader to be wowed by a topic, then you might use a voice of awe or excitement, or a very dramatic voice. Here are just a few examples of voice from some of my favorite nonfiction picture books:

“Shrinking planet. Streaming fast. Starry darkness. Sprawling, vast.”

Linda McReynolds, in Eight Days Gone, uses terse verse to create a tense and dramatic telling of the first lunar landing.

“Feathers can distract attackers like a bullfighter’s cape… or hide a bird from predators like camouflage clothing.”

Melissa Stewart uses similes in every listing in Feathers: Not Just for Flying. Her straightforward language is a great contrast to the surprising comparisons she makes, and it keeps the book very kid-friendly and easy to understand. In Noah Webster’s Fighting Words, Tracy Nelson Maurer lets Noah speak for himself in a rather arrogant tone. It tells us about his personality and also make great comic effect throughout the book.

“Noah’s spelling book became America’s first best seller.” Noah’s ghost edits to add: “For the record, my speller has sold about 100 million copies—one of the top sellers ever in American publishing history. Not surprising, I say.”

In Round, Joyce Sidman uses gorgeous, lyrical language to create a sense of quiet and wonder. Here, the narrator describes the moon:

“Or show themselves, night after night, rounder and rounder, until the whole sky holds its breath.”

DO THIS NOW

- Have someone read your manuscript aloud to you. Think of a word to describe the voice or tone of the piece. Is it lyrical, irreverent, awestruck, angry, dramatic, determined? Something else?

- If you couldn’t hear any “voice” in your piece, or if the voice that came through doesn’t really match your goal for your book, then it’s time to revise. Choose a single word that you want to describe your voice in this particular book.

- Write a new draft, looking for every opportunity to make your voice stronger. Writing picture books is often compared to writing poetry, because you have to pay attention to every single word.

- If you’re struggling with voice, ask your writer friends to recommend picture books with a ________ voice. Check out the books. Read them. Analyze them. Besides word choice, look at sentence length. Study pauses. Listen to how the words sound, too—are they full of /ō/ sounds, which give a lonely mood to a piece? Do you use a lot of words with hard sounds, like /k/ and /p/? That supports a strong declarative, emphatic voice, but not a lyrical voice.

Step 11: Imagine Storytime An important quality of picture books is that they are usually read aloud to kids. Some things that can give a book more read-aloud appeal are:

Step 11: Imagine Storytime An important quality of picture books is that they are usually read aloud to kids. Some things that can give a book more read-aloud appeal are:

- its interactive potential: Are there questions the listener might answer? Is there a repeated refrain?

- its rhythm: Some books slip off your tongue like silk and are a delight for the person reading aloud.

- its language: Are there some surprising words in your manuscript?

- its actions: Are there motions or actions that listeners can do?

- its clarity: Picture books NEED the illustrations—that’s part of what makes them picture books. But is your manuscript’s meaning clear, even for the kids at the back of the crowd who can’t see the art?

- its voice: A strong voice in the text makes a better read-aloud, because the tone of the writing itself gives the person reading great clues for how to read it.

- the mystery: Is there a sense of drama at the page turns? Will you have kids saying, “What is it? What is it?”

- its staging: Is your picture book able to be acted out in a Reader’s Theatre style? Are there different characters with distinct personalities and, presumably, speaking voices?

Your manuscript won’t and shouldn’t have ALL of these! But a picture book that lends itself to being read aloud is a great goal. NOTE: There are exceptions, such as the occasional longer nonfiction picture books that are more than 1,000 words (like Island or Grand Canyon, both by Jason Chin). Those are often used in older classrooms or, if they’re read aloud to younger kids, they might not be read all in one sitting in a storytime style.

DO THIS NOW

1) Read your book aloud. Note where you stumble. Fix those places.

2) Imagine sharing your book with a group of 15 or 20 kids. How would you engage the kids in your reading?

3) Is there an opportunity for a refrain or for questions? In other words, is there anyplace you can imagine kids calling out because they know what’s coming or they know the answer and they want to tell you?

4) Choose one of two of the above elements to focus on write a new draft!

Here’s something kind of funny. Back in the early stages of this process, I was brainstorming possible angles for writing a picture book about trucks or truckers. Not to really do it, but in order to share examples of how I approach things. A couple of days ago, I was Ubering home from the library, and my driver mentioned trucking. He used to be a long-distance trucker! Even though I don’t really plan to write about this topic, it seemed like destiny. I asked him all sorts of questions about how long-haul truckers live on the road. I learned several interesting things that were tiny pieces of a possible story. I thought this was a great example of how a topic might stay on the back burner of your mind for weeks, months, or many years, and you might learn little tidbits of things that eventually all tie together into a cohesive book.

Here’s something kind of funny. Back in the early stages of this process, I was brainstorming possible angles for writing a picture book about trucks or truckers. Not to really do it, but in order to share examples of how I approach things. A couple of days ago, I was Ubering home from the library, and my driver mentioned trucking. He used to be a long-distance trucker! Even though I don’t really plan to write about this topic, it seemed like destiny. I asked him all sorts of questions about how long-haul truckers live on the road. I learned several interesting things that were tiny pieces of a possible story. I thought this was a great example of how a topic might stay on the back burner of your mind for weeks, months, or many years, and you might learn little tidbits of things that eventually all tie together into a cohesive book.

Step 12: Cut It: The Long and Winding Read This series is about nonfiction picture books. There are longer nonfiction books for middle-grade (4th-6th grade) readers, and those books are illustrated or photo-illustrated. But I’m not talking about those books in this series. I’m really talking about picture books for up to 2nd or 3rd grade at the oldest. Here’s a truth about picture books and the current publishing industry: shorter is more in demand and is more salable. I love short picture books, so I’m happy about it. Other readers and writers long for the days when lush, detailed stories were the norm in picture books. No matter which camp you fall into, the facts are the facts. So if your goal is to write a picture book that has a better chance of selling to a publisher and then to readers, you need to pay close attention to length. Aim for no more than 800 words, and that’s if you’re writing a picture book for school-age kids. If your book is meant for toddlers and preschoolers, it will need to weigh in at just a couple hundred words, probably. I’m talking about the main text here. If you’re using layered text (see Step 6: Structure It), you might be adding sidebars or additional text on each spread that is “optional reading.” For right now, just focus on the main text: the text that every person who reads/hears the book will read. Here are the word counts of the main text for a few of my nonfiction picture books—note that all of these have a core audience of K‑2 (kindergarten through 2nd graders).

| Title | Main Text Word Count (approx.) | Sidebars/ Layered Text (approx.) | Backmatter? (besides glossary/ suggested reading) |

| Snowman-Cold=Puddle | 95 | 800 | Author’s note, when spring starts |

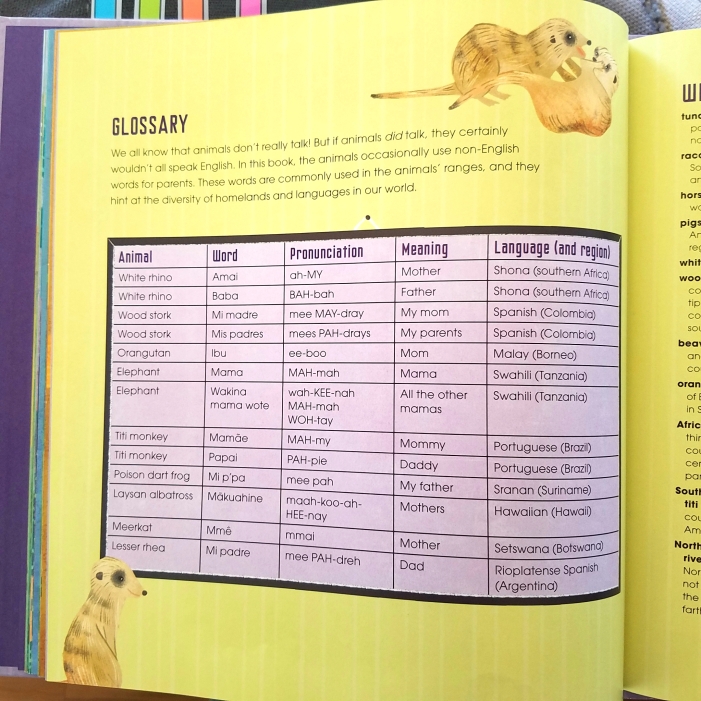

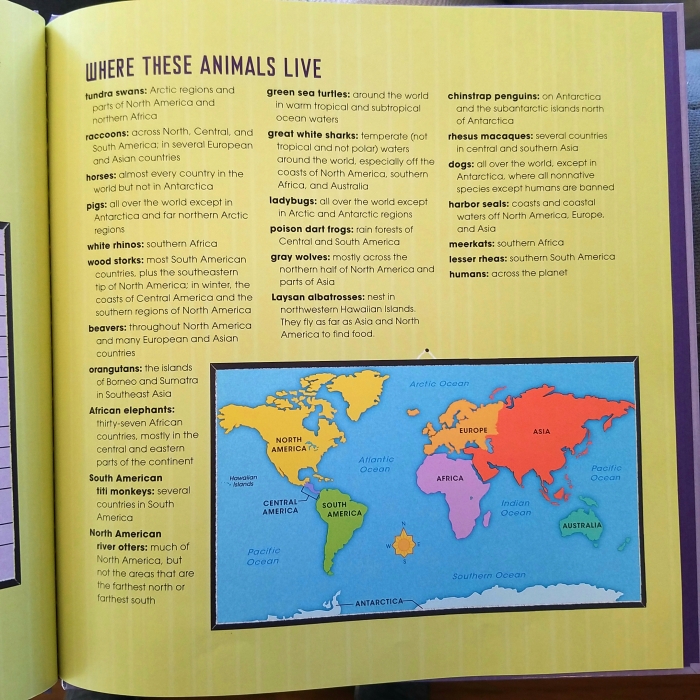

| Meet My Family | 150 | 800 | Language chart, animal range map |

| If You Were the Moon | 128 | 720 | None |

| A Leaf Can Be… | 110 | 0 | Brief paragraph about each role |

So, what if you check your word count and discover your main text is 1500 words—or longer? You cut. You cut a lot. In fact, you might need to rethink your approach and go back to one of the earlier steps, because chances are you’ve tried to cover too much information for this young age range. Maybe you took too broad or encyclopedic of an approach. Or maybe you had a good angle but just went into too much detail. You might want to try a whole different structure or approach. Or you might want to think about separating out the bare bones, crucial info that can be your main text, and think of an approach that incorporates some of the remaining text into sidebars or backmatter. Please know that trying multiple different approaches to figure out the one that “fits” into the picture book format. Or maybe your manuscript is too long, but not ridiculously long. In that case, ask yourself, what is my single, specific idea for this book? Then read through your text, asking yourself after every single paragraph, “Is this information necessary to the specific idea of this book?” If not, cut it. Ruthlessly. You can also think about what information can be shown through images and illustrations (more on this in an upcoming step). As with fiction picture books, these projects are true collaborations! The art does not just support the text. It works with the text, working equally to convey information to your reader. In If You Were the Moon, for instance, my main text line of “Challenge the ocean to a tug of war” does not clearly tell the reader everything that spread conveys. But the art, showing the moon and the swell of the ocean, helps get the idea of gravity and tides across. And the sidebar text spells it out even more clearly.

Sometimes we forget to leave room for the illustrations or photos, but they can do some of the heavy lifting. So leave some of those big boxes for them to carry. If your book is a narrative—a biography or a story of an event—you might need to cut some events out. Telling a nonfiction narrative is as much about what you leave out as what you choose to keep in. Remember that you can never tell all the truth of any event or topic. So even if you’re telling the story of a true event, you still have to figure out your specific angle—what approach YOU’re taking to telling that story. What YOUR key idea is that will help guide what you cut and what you keep. Your goal at this point isn’t a final polish. But you should be getting your manuscript into a structure now that makes it easy to hit your word count limit.

DO THIS NOW

1) Check the word count of your manuscript.

2) Is it too long? Usually, the answer will be yes. Don’t feel bad.

3) Determine whether you need to try some new structures/approaches.

4) Brainstorm some ways you might use layered text or backmatter to lighten up your main text.

5) Identify spots where you can cut text and allow images, charts, or diagrams to convey information.

6) Write a new draft. Or six.

Step 13: Storyboard It By this time, you hopefully have a draft that is a reasonable word count and feels like the right structure for your book. Now it’s time to storyboard. This is also called dummying out a story. The idea is to figure out what text (and possible) image will go on each spread of your book. Picture books are generally 32 pages (though there’s a lot more variety in length than there used to be). So I typically am breaking down my story into 14 spreads, plus possibly a single page at the front and back. In nonfiction storyboarding, I usually leave at least one spread for backmatter (more on that in the next step).

Here are several things I’m looking at when I storyboard.

- Does each spread end with text that makes me want to turn the page and see the next spread?

- Is there too much text on each spread? (Sometimes, a manuscript is in the “right” word count range, but I realize upon storyboarding that it’s way too text-heavy.)

- Are there a great variety of illustration possibilities? I am a terrible draw-er, but I make some kind of graphic sketch of what might happen on each spread. If I realize I’m drawing the same thing over and over, then I have a problem with pacing and/or plot.

- What is the overall arc of my book? How long am I spending on an introduction? How long on the conclusion? Where is the emotional high point of the manuscript? Does it happen too early in the book?

- Does the rhythm of my text work okay?

- Am I having to cram in multiple events on one spread? If so, I might have too much detail in my manuscript.

- Are there places it might work to build in tension by trailing off the text at the end of one spread and finishing the thought on the next? Or by asking a question to engage the reader at the end of one spread and answering it on the next? A key component of the picture book format is the page turn. Are you using page turns to the fullest?

Here are a few of my storyboards. I don’t usually take pictures of them, so the photos were slim pickings!

See? It doesn’t matter how bad your storyboard looks! You won’t be sending it to an editor when you submit your manuscript. And the editorial team might decide to break up the text differently than the way you did. That doesn’t matter. The dummy or storyboard is simply a tool to help you ensure that your manuscript works within the confines of this form.

DO THIS NOW

- Watch the video I linked to and choose a storyboarding method.

- Storyboard your manuscript and go through my bulleted points.

- What possible issues did your storyboard reveal?

- Figure out your next step to solving those issues. (And, yes, this sometimes means going back to an earlier step and trying a new structure, or choosing a new angle.)

- Get going!

Step 14: Come On Back(matter) Backmatter is, not surprisingly, matter that’s at the back of a book. Most nonfiction picture books have them, and educators especially love them! Basically, backmatter might be anything that extends the topic and learning further for the reader. Here are some fairly common kinds of backmatter:

Step 14: Come On Back(matter) Backmatter is, not surprisingly, matter that’s at the back of a book. Most nonfiction picture books have them, and educators especially love them! Basically, backmatter might be anything that extends the topic and learning further for the reader. Here are some fairly common kinds of backmatter:

- author’s note

- illustrator’s note

- a further reading list

- fun facts

- glossary

- diagrams

- historical photos

- timeline

- charts to more fully explain concepts

- a more in-depth look at the topic (backmatter might be longer than the entire main text, in fact)

- activities/experiments

If you’ve been reading lots of nonfiction pictures (you have, right?), then you’ve seen plenty of examples. I have started a “backmatter is interesting” shelf on Goodreads, which I’m trying to remember to add books to when appropriate. You can check it out to see some good examples of different kinds of backmatter. Also, know that it’s great to think about backmatter as you write your manuscript. And you should keep track of fun facts and cool things you come across that don’t fit in your main text. But you don’t necessarily have to have it completely written before submitting your work. The editor’s opinion, the topic, the number of pages, and more will all impact your backmatter. I often simply include a line in my query or cover letter (or right at the end of the manuscript) that says something like, “Possible backmatter options include a timeline of the major events, an explanation of the basic artistic styles, a glossary, and a list of further reading. It might also be fun to include a simple, adaptable art project.” Here are pictures of the backmatter in Meet My Family! This is my newest picture book, and the backmatter for it is more in-depth than any I’ve done before.

DO THIS NOW

- Identify at least five books with backmatter that you really enjoyed.

- Brainstorm at least four possible backmatter options for your manuscript.

Step 15: Get Feedback At some point along the path of writing your nonfiction picture book, you will need to get feedback. Perhaps at many points. My writing group, the Wordsmiths, meets monthly, and as we pass out our manuscripts, we often introduce them with, “The LAST time you saw this, it was…” You might get feedback from a critique group or from a paid editor. Both can be valuable. What is typically not valuable is feedback from people who love you or who are sitting on your lap when you share your manuscript. These folks love the experience of being with you and having you read. That colors their ability to give you useful feedback on your manuscript. Here’s a bit more advice on feedback, from my book Making a Living Writing Books for Kids:

No matter how far along you are in your writing career, feedback is useful. I’m a pretty flexible person, and when I do dancer pose (a yoga pose), it feels like my back leg is reaching into the clouds. But if I’ve been sick or stressed, my back leg feels like it’s dragging through a bog. I decided to see what the reality was. I couldn’t trust what I felt. I needed a clinical, disinterested observer: a camera. When I took a picture of myself, I discovered my dancer pose is somewhere in the middle. Not in the clouds. Not in the bog. Like most of my manuscripts. It’s almost impossible to evaluate our own manuscripts. I’ve been writing a long time, and it’s still impossible. The only way I can see my work with a clear, evaluative eye is if I let it sit, out of sight and out of mind, for so long that I honestly don’t remember even writing it. That takes two to three years, and I am not that patient! So I seek out honest feedback, usually, from my writing group (go, Wordsmiths). These critique group buddies keep it real. They help me nudge good drafts even higher. And they help me pull the mucky ones out of the bog. Occasionally, they just offer support as I give the wretched mess a good burial. No matter what, they help me see the truth of my own writing. And that’s the first step toward making my writing stronger. Other times, my agent or editor or a trusted paid critiquer has provided the first feedback on a manuscript after I’ve gotten it into the best shape I can on my own. No matter where the feedback is coming from, I can benefit—my writing can benefit—from fresh eyes and honest comments.

Get Ready for the Gut Punch

Here’s the thing. In order for feedback to lead to an improved manuscript, you have to actually hear it! I heard a podcaster compare getting feedback to being gut-punched. But feedback is a punch I ask for, so I tighten my abs and prepare for it. And I don’t whine. Because if I ask for feedback and then reject it all, what’s the point? Lisa Bullard and I had a coaching/critique service called Mentors for Rent, and many of our clients were at the very beginning of their writing journey. They had a lot to learn about writing for kids—and that was great. They wanted to learn. They took the feedback. They asked questions. I always have hope for those writers! But there were also writers who interrupted every five seconds to explain why they did something, why it was right and we were wrong, and so on. They were unwilling to accept feedback. Afterward, I would wonder why someone paid good money to get feedback they didn’t want to hear. I was a Creative Writing major in college and participated in hundreds of writing workshops—listening to 20 other people say what worked and didn’t work about my manuscript. And I was not allowed to say a word during their feedback. Not. A. Word. It was so hard—but really illuminating. Before you ask for feedback, ask yourself if you really want it—if you’re open to change. If so, great! Then tighten your abs and get ready. Writing is about communicating with readers. You should be keenly invested in ensuring your writing is communicating exactly what you want it to. If you don’t want feedback, a career as a writer probably isn’t for you.

And just so you know, I have published more than 120 books, and I still get plenty of feedback! Here’s a blurred picture of one page of a picture book manuscript from my critique group yesterday. See all those lovely marks letting me know where my story is not quite working?  Okay, your turn!

Okay, your turn!

DO THIS NOW

- Find 4 or 5 people to give you honest feedback about your manuscript. Double points if some of them are professional writers. Do NOT try to convince them why your manuscript is right and they are wrong.

- Let their feedback sit for a week or two to let any emotional sting wear off.

- Reread your manuscript with their feedback in mind. Identify the suggestions that resonate with you and the ones that don’t.

- Map out a plan for your revision. (What do you plan to change? How? Why?)

- Dive in!

Step 16: Circle Back It’s no coincidence that these last three steps have “back” in them. Backmatter, feedback, and circling back are all important steps in this project. So, you’ve now gone through all the steps of writing a nonfiction picture book. Is your picture book ready to submit? Probably not. I know I’m repeating myself, but it fits this step. Writing is recursive. You rarely complete the steps once and in order. You will end up going back to repeat steps or expand on your earlier efforts. You will try different approaches and get feedback from new people. You will look at language many times over the course of writing a book. Writing a book is exciting, wonderful, and sometimes utterly confusing. I have picture book manuscripts that took only a few weeks to write (a rarity) and picture book manuscripts that took months (common) or years (also common) to find their proper form and voice. And I’m sad to say that I have a number of back-burnered manuscripts that either 1) haven’t yet found their proper form and voice or 2) are exactly right (in my opinion) but are unmarketable (meaning no publisher thinks they can sell enough copies to be worth the investment). So, first, take a moment and celebrate that you’ve gotten this far in the process!

Step 16: Circle Back It’s no coincidence that these last three steps have “back” in them. Backmatter, feedback, and circling back are all important steps in this project. So, you’ve now gone through all the steps of writing a nonfiction picture book. Is your picture book ready to submit? Probably not. I know I’m repeating myself, but it fits this step. Writing is recursive. You rarely complete the steps once and in order. You will end up going back to repeat steps or expand on your earlier efforts. You will try different approaches and get feedback from new people. You will look at language many times over the course of writing a book. Writing a book is exciting, wonderful, and sometimes utterly confusing. I have picture book manuscripts that took only a few weeks to write (a rarity) and picture book manuscripts that took months (common) or years (also common) to find their proper form and voice. And I’m sad to say that I have a number of back-burnered manuscripts that either 1) haven’t yet found their proper form and voice or 2) are exactly right (in my opinion) but are unmarketable (meaning no publisher thinks they can sell enough copies to be worth the investment). So, first, take a moment and celebrate that you’ve gotten this far in the process!

And now…time to get back to work. Your job now is to figure out what your particular manuscript needs most and try to do that. That will mean circling back around to some of the steps you’ve already gone through and digging back in. This does NOT mean you failed at the step before! Circling back is simply the way the writing process works. It is the way writers work. At some point, you will feel the book is the very best you can make it. You will have taken feedback and used it to make your manuscript stronger. You will have poured your passion and energy and time into writing and rewriting. You will have polished every word until it sparkles. And then you will be ready to start your agent or editor hunt. And please know that, as you get feedback from agents or editors, you might find yourself circling back to these steps again!

Thanks for coming along on this journey. I hope you’ve found this series of posts helpful! Best of luck with your nonfiction picture book–I hope it finds its way out into the world someday!